The Lancet Report on the 10th International Medical Congress in Berlin1890

Malling-Hansen-inspired physiological research continued by Swedish scientists

Research, transcription and comments by Jørgen Malling Christensen.

The text transcribed below is from The Lancet of August 16, 1890, reporting on the proceedings of the International Medical Congress which took place in Berlin August 4-9, 1890. Rasmus Malling-Hansen did not participate – at the time he was very much occupied with the Jonstrup centenary festivities, celebrated principally on August 4, in addition to the 6th Nordic School Meeting in Copenhagen August 8-12. At both of these occasions RMH had – in spite of his serious health problems during the first half of 1890 – a key role as speaker and organiser. However, two of his Swedish friends and colleagues participated in the 1890 congress, i.e. Ernst Axel Henrik Key (1832-1901) and Erik Wilhelm Wretlind (1838-1905) – both of them giants of the Swedish medical scene at the time and both men very much concerned with the welfare of school students – just like Malling-Hansen was! The two Swedish scientists also had in common that they admired Malling-Hansen’s research, followed in his footsteps and to some extent broadened the scope of this line of research.

Dr. Key was a pathologist, a member of the Swedish parliament, a prolific writer and also dean of the prestigious Karolinska Institute. Key set up Sweden’s first pathological laboratory at Karolinska and is credited with having introduced cellular pathology in the Swedish medical science. He worked hard to improve hygiene and the general welfare of primary and secondary school students. Axel Key participated in the 1884 Medical Congress in Copenhagen as a Swedish delegate and became very much impressed by Rasmus Malling-Hansen’s presentation and research results. In his own research he continued the same line of focus, similar to the other contemporary giant of Swedish medical research, Erik Wilhelm Wretlind, who undertook such research for several years at schools in Gothenburg and surroundings, measuring an weighing thousands of school students.

Two generations after Key and Wretlind another important Swedish medical physician and researcher, Karl Gustav Vilhelm Nylin (1892-1961) stepped directly into Malling-Hansen’s footsteps and replicated his methods and approach in an ambitious study which was to become his PHd-thesis, succesfully defended in 1929: “Periodical Variations in Growth, Standard Metabolism and Oxygen Capacity of the Blood in Children”. His results from the 1920s environment of a Stockholm suburb confirmed Malling-Hansen’s findings!

The following text appeared in the LANCET edition of August 16, 1890, reporting on Dr. Key’s address at the 1890 Medical Congress in Berlin, and although it only mentions Malling-Hansen’s name once, it is still worth keeping on record since Dr. Key is building on and continues Malling-Hansen’s scientific research tradition. Key’s presentation was entitled: “Die Pubertätsentwicklung und das Verhältnis derselben zu den Krankheitserscheinungen der Schuljugend”.

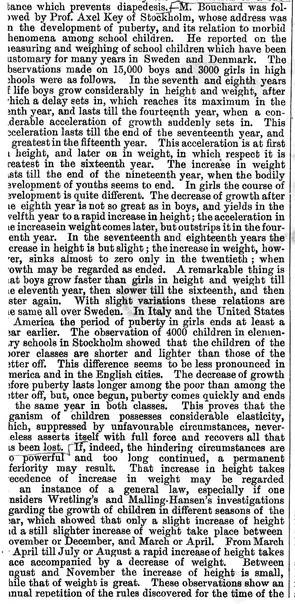

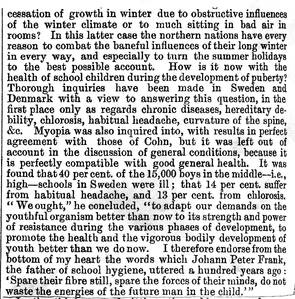

-----M. Bouchard was followed by Prof. Axel Key of Stockholm, whose address was on the development of puberty, and its relation to morbid phenomena among school children. He reported on the measuring and weighing of school children which have been customary for many years in Sweden and Denmark. The observations made on 15,000 boys and 3000 girls in high schools were as follows. In the seventh and eight years of life boys grow considerably in height and weight, after which a delay sets in. This acceleration lasts till the end of the seventeenth year, and is greatest in the fifteenth year. This acceleration is at first in height, and later on in weight, in which respect it is greatest in the sixteenth year. The increase in weight lasts till the end of the nineteenth year, when the bodily development of youths seems to end. In girls the course of development is quite different. The decrease of growth after the eighth year is not so great as in boys, and yields in the twelfth year to a rapid increase in height; the acceleration in the increase in weight comes later, but outstrips it in the fourteenth year. In the seventeenth and eighteenth years the increase in height is but slight; the increase in weight, however, sinks almost to zero only in the twentieth, when growth may be regarded as ended. A remarkable thing is that boys grow faster than girls in height and weight till the eleventh year, then slower till the sixteenth, and then faster again. With slight variations these relations are the same all over Sweden. In Italy and the United States of America the period of puberty in girls ends at least a year earlier. The observation of 4000 children in elementary schools in Stockholm showed that the children of the poorer classes are shorter and lighter than those of the better off. This difference seems to be less pronounced in America and in the English cities. The decrease of growth before puberty lasts longer among the poor than among the better off, but, once begun, puberty comes quickly and ends in the same year in both classes. This proves that the organism of children possesses considerable elasticity, which, suppressed by unfavourable circumstances, nevertheless asserts itself with full force and recovers all that has been lost. If, indeed, the hindering circumstances are too powerful and too long continued, a permanent inferiority may result. That increase in height takes precedence of increase in weight may be regarded as an instance of a general law, especially if one considers Wretling’s and Malling-Hansen’s investigations regarding the growth of children in different seasons of the year, which showed that only a slight increase of height and a still slighter increase of weight take place between November or December, and March or April. From March or April till July or August a rapid increase of height takes place accompanied by a decrease of weight. Between August and November the increase of height is small, while that of weight is great. These observations show an annual repetition of the rules discovered for the time of the external influences, such as school arrangements. Is the cessation of growth in winter due to obstructive influences of the winter climate or to much sitting in bad air in rooms? In this latter case the northern nations have every reason to combat the baneful influences of their long winter in every way, and especially to turn the summer holidays to the best possible account. How is it now with the health of school children during the development of puberty? Thorough inquiries have been made in Sweden and Denmark with a view to answering this question, in the first place only as regards chronic diseases, hereditary debility, chlorosis[1], habitual headache, curvature of the spine, &c. Myopia was also inquired into, with results in perfect agreement with those of Cohn[2], but it was left out of account in the discussion of general conditions, because it is perfectly compatible with good general health. It was found that 40 per cent of the 15,000 boys in the middle – i.e. high – schools in Sweden were ill; that 14 per cent suffer from habitual headache, and 13 per cent from chlorosis. “We ought,” he concluded, “to adapt our demands on the youthful organism better than now to its strength and power of resistance during the various phases of development, to promote the health and the vigorous bodily development of youth better than we do now. I therefore endorse from the bottom of my heart the words which Johann Peter Frank[3], the father of school hygiene, uttered a hundred years ago: ‘Spare their fibre still, spare the forces of thier minds, do not waste the energies of the future man in the child.’”

[1] JMC: Also called ’greensickness’, a benign type of iron-deficiency in adolescents, marked by a pale yellow-green complexion.

[2] JMC: Herman Cohn, German ophthalmologist; in 1866 Cohn published his study of the eyes of 10 000 children attending the schools of Breslau. His conclusion was that myopia was caused by use and abuse of the eyes. Cohn’s theory dominated for the next 50 years and a crusade began for better conditions of visual hygiene in schools. Later on, other researchers put forward other causal theories, including hereditary causes.

[3] JMC: Johann Peter Frank, 1745-1821, German physician and hygienist. Frank was an important figure in the early history of social medicine and public health.