What did the very first writing ball look like?

Most writing ball cognoscenti regard the well-known wooden box model from 1870 with an in-built cylinder as the very first writing ball. This model had the paper attached around a cylinder that moved by means of an electrical battery. The wooden box model was displayed to journalists and people in the trade in Denmark on September 8, 1870, receiving good coverage in the press already the following day. Many have considered this to have been the prototype of the Malling-Hansen writing ball.

- This illustration of an early model of the writing ball confirms that Malling-Hansen probably built several different specimens of his invention before ending up with the first official model in 1870. This table model is shown on an American poster from 1888 published by Butterworth. Unfortunately it is not possible to verify if the illustrations is based on an existing model, or is just the illustrators imagination of how a model might have looked like. The poster was shown in the journal ETCetera in their issue in March 1997.

From diary notes written by Rasmus Malling-Hansen’s brother-in-law, Johan Alfred Heiberg, we know that the two of them experimented with the placement of the letters on the ball keyboard already in 1865, but we don’t know for sure how far RMH had advanced with the process of building his first writing ball at that time. The current speculation has been that he was only focusing on the “ball head” during these first years, but in my view it does not appear likely that a person who is about to invent one of the very first machines in the world with which to type letters would spend several years merely in order to find out how best to place the letters on the keyboard. It would seem as unlikely as if, e.g., the person who invented the world’s first motor vehicle would spend several years designing the dashboard before beginning to think about where to place the wheels and how to construct the steering mechanism etc. It is more likely that RMH had a clear idea about the features and working mechanism of the entire writing ball before starting to experiment with details such as where to place each individual letter. The fact that workshop drawings of the writing ball from this period – around 1865 – have not been preserved or found does not mean, of course, that such drawings did not exist at the time. From RMH’s son-in-law, Michael Agerskov, we know that RMH himself destroyed most of the preparatory materials and notes related to his work about the growth of children in cycles posterior to the publication of the books, and presumably he did the same with his preparatory work related to the writing balls – unfortunately.

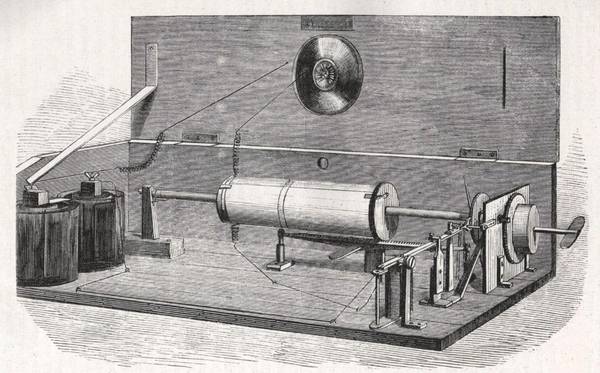

We must assume that RMH worked continuously from 1865 and until the end of the 1860s to construct a fully workable typewriter. We do not know how many years it took for him to finalize the first prototype, and he did not present his first patent application until January 25, 1870, when he showed two different models. One model had the paper fastened on a flat frame that could be pushed forward by manual power for each new line, while the writing ball, that could be moved horizontally across the paper surface by means of a wheel on rails, had to be pushed aside with one hand while punching the keys with the other hand. The second model was built into a table, the paper being fastened to a cylinder wound by pedal power. Using one foot one would set the cylinder rotating very slowly and pressing down the keys at a frequency corresponding to the rotational speed of the cylinder, such that the letters were placed at an even distance after each other. It demanded quite an extraordinary precision and accuracy to have the letters placed with identical space between each other, and no typing samples have yet been found from these early writing balls. But that doesn’t necessarily imply that they were not built, because at least one of them was put together, according to RMH himself!

- Patent drawing from January 18, 1870. The drawing shows two different models of the writing ball. Below is a model where the cylinder to which the paper is attached is propelled by means of the typist’s foot, pressing a pedal in order to rotate the cylinder. The other model is shown on the two drawings of a frame with a handle – to the left it is seen from above and to the right from below. The paper guiding was manual. I have numbered these two models as writing ball models no 1 and 2, respectively.

It is also worth noting the very thorough assessment of the factors that might contribute to bringing about the best typing speed, being the basis of the shape of the keyboard of the writing ball. RMH documented that he had taken into consideration the most frequently used letters[1] and their placement in relation to which fingers are capable of writing most speedily, as well as seen to having letters used in the most frequent letter combinations were not to be typed by the same finger. The short pistons placed at a certain individual angle through the writing ball hemisphere, as well as the shape of the pistons, would also contribute to a high-speed typing, and also minimize the risk that the pistons would become entangled. This feature was in great contrast to the competing Remington-machine, where the only criteria by the placement of the keyboard letters was that the letters most frequently succeeding each other in the English language, had to be placed as far away from each other in order to avoid that the very long, jointed pistons would entangle. The typing speed did not enter the equation at all in that context.

However, how can I with such confidence state that at least one of the models described in the patent text of January 25, 1870, was built? Well, because RMH himself tells us so. It is perfectly clear from the patent application text that at least one of the models was in fact finalized, and most probably both of them, since Malling-Hansen writes as follows:

“with these investigations and tests as a foundation I started putting together a machine for speed writing, and this machine eventually acquired the shape that I have tried to illustrate in the enclosed drawings and which I shall try to describe in detail in the following.”

Hence, there can be no doubt that the writing balls on the patent drawings of January 1870 must be recorded not only as fore-runners of the writing ball being presented to the press in autumn 1870 but really independent prototypes that existed not only on paper. Through various sources, among them in articles by the son-in-law Fritz Bech, as well as by some of RMH’s daughters, we are informed that the very first writing ball model weighed around 75 kilos. This would indicate that Malling-Hansen himself counted the large model built into a table as the very first writing ball model. Judging by the drawing it seems reasonable to suppose that the weight was around 75 kilos. Those of the opinion that RMH did not build any writing ball prior to presenting his patent application and that the wooden box model with the battery must be regarded as the prototype have judged that the weight of 75 kilos must have included the battery, because the wooden box with its content weighed only some 9 kilos. However, a closer investigation into the batteries available at the time has shown that that there were in fact wet batteries already from 1866, used in telegraphy stations and for telephones, and these batteries are not particularly voluminous – rather they resemble jam jars filled with liquid, and they seem to have weighed less than 10 kilos. Hence, the size of the batteries cannot explain the large weight of the first writing ball.

[1] JMC: Meaning: the most frequently used letters in Danish (and Norwegian). This is not a trivial issue in the assessment of the RMH writing balls and their competition with the Remington machines; with hindsight: had RMH considered and prioritized the English-speaking market, he would have had to re-position the keyboard letters so as to fit the frequency of the letters as they are used in American and British English. That small adaptation, combined with a better understanding of the American market, could very well have been decisive for the outcome of the battle between the various brands of typewriters.

- The Danish Consul in New York, General Christian Thomsen Christensen, 1832 – 1905, was a valuable supporter for RMH in USA.

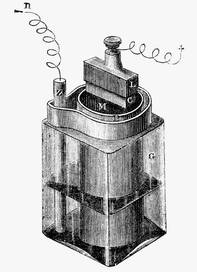

- Georges Lionel Leclanché, 1839-1882, in 1866 invented a wet battery that became very popular and was produced in several thousands of copies.

- The French as well as the Belgian telegraph companies used this type of batteries at their stations, and they were also used for telephones, since telephones in this period of time could not draw electricity from the telephone line. Comparing the Leclanché-batteries above with the batteries in one of the first models of the writing ball shown in the graphic print below, one will note a very clear resemblance .

It is likely that both these models, rendered in the drawings, were in fact built, because from one of the letters from July 26, 1870, from RMH to the Danish Consul in Washington, USA, general Christian T. Christensen, we know that he favored working with several models simultaneously:

“The machine itself, as well as two other such machines with modifications, will be ready in a few days. They correspond entirely to my expectations. I shall very soon permit myself to send your Grace samples of the work of the writing ball. The arrangement of the electrical machine to move the platen has undergone many changes for the better since the last time your Grace was here”.

My interpretation is that RMH, at this point in time, saw the electrical wooden box model as the writing ball that he was going to invest in and develop further, while simultaneously working with two other machines, which were further developments of previous models. In actual fact he himself hardly carried out this work, rather his mechanic and – in certain considerations co-inventor – C.P.Jürgensen – performed it in practice .

Already within a week after the first patent application, on January 31[1], 1870, RMH presented a supplement to the original text, the paper feed mechanism being the object of further development. Very soon he found a way to make the movement of the paper happen automatically every time a key was pressed, making use of a helical spring that was wound up before the machine was to be used. The depression of a key then made the spring trip a movement of the cylinder, precisely big enough to make another letter appear at exactly the right distance from the previous one. The solution of this model in relation to the paper guide could be characterized as being based upon a solution somewhere between manual, pedal and electrical power, and as such had to be wound up pretty much like a mechanical toy vehicle before it could be used.

[1] JMC: According to the leaflet: “Who is the Inventor of the Writing-Ball?” (Copenhagen 1925, in Danish) by RMH’s daughter Johanne Agerskov , she quotes a letter by a Mr B.Adler sent to Professor Hannover in relation to the controversy about the Peters’ “writing ball” and Prof Hannover’s claim that Peters was two years earlier with his invention (1868) than RMH: “In this letter Mr Adler, a whole-sale dealer, confirmed that he had seen during his Christmas vacation either 1866-67 or during Christmas 1868-69 a writing ball shown by RMH at the Institute for the Deaf-Mute”. This was an information provided to Johanne Agerskov by Mr Adler in 1924 and hence it was not easy for the informer to be absolutely sure about the year. However, he was absolutely certain of having seen the writing ball before 1870! Furthermore, on page 60-61 she relates the written testimony of RMH’s brother-in-law I.A. Heiberg, confirming that he witnessed and took part in RMH’s experiments with the porcelain hemisphere that took place at Keldby, Møen, in April 1865. The memory is very detailed regarding Heiberg assisting RMH in his tests about how quickly he could type the various letters in different combinations. He also confirmed that these memories were noted down in his diary from 1865.

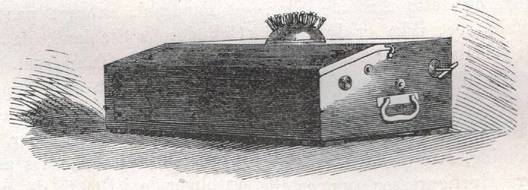

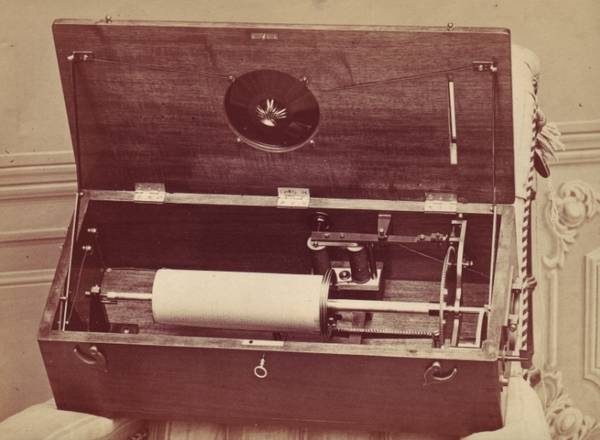

- The two containers to the left inside the wooden box of this writing ball are in all likelihood two wet batteries in the shape and style of the ‘Leclerché’s wet cell’, as it was called. Note also the “key” sticking out on the right hand side. According to one of the supplements of RMH’s first patent application this key was used to wind up a helical coil that served to move the paper guide one notch around for each letter pressed down. This “combination model” was described for the first time in the supplement from February 28. The illustration was used in many journals and magazines in the first part of the 1870s.

In the second supplement, dated February 28, RMH includes the information that the cylinder could also be moved by means of an electromagnet in combination with a “watch spring”, as described in the first supplement. There is much circumstantial evidence that this combination model, capable of using electricity as well as a helical spring, was really built because graphical prints were made of it, and the illustration was used in several magazines in 1870. This version of the writing ball was also built into a wooden box, similarly to the “officially” first version, but its wooden box featured a tilted surface at the side turned towards the typist – for him or her to rest the arms -, and it was also equipped with a key at one end for winding up a spring mechanism. However, as RMH himself described it in his letter to general Christensen in the USA during the Summer of 1870, a further development of the electrical solution was taking place, and the “official” writing ball demonstrated in public in Autumn 1870 no longer had internal batteries, but rather a switching-on point on the outside of the wooden box. Inside the box were also two coils or reels wrapped with copper wire such that the electricity from the battery was transformed into magnetism used for the movement of the paper platen as triggered by the suppression of the keys and pistons.

Throughout the 1870s RMH developed the cylinder model as well as the flat model, and already in 1871 he launched new, open writing balls with a cylindrical as well as with a flat paper surface, until finally in 1875 he abandoned electricity all together and launched the very first high model, where he had chosen what we may call a compromise solution between the cylinder-shaped and the flat paper surface, where the paper was fastened onto a curved frame. At this time, batteries were not 100% reliable and required quite a lot of maintenance and inspection, and RMH had for a long time been searching for a better solution for the paper guide, since he – according to his son-in-law Fritz Bech – had frequent complaints from buyers of the writing ball on the ground that the battery had stopped working. Consequently, RMH had asked his mechanics to find a solution that would automatically move the paper frame a step ahead each time a key was depressed; however, they were not able to find a satisfying solution, and hence – according to Fritz Bech – the inventor himself had to step in and come up with the final solution.

- An old picture of what has up until now been regarded as the very first writing ball, but was in all likelihood in reality writing ball no 5. Note the two hasps, wound with copper wire in order to cause magnetism. However, RMH did not stop his quest at this model. He continued to develop his writing ball up until his last model, designed for the world exhibition in Paris in 1878. After that point in time, the master mechanic August Lyngbye took over the continued development of the writing ball. He also advertised with having made writing balls featuring upper-case as well as lower-case letters.

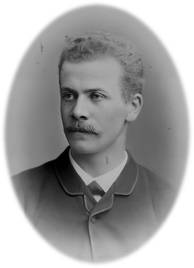

Three persons of great importance to the development of the writing ball. From left: Malling-Hansen’s son-in-law, Johan Alfred Heiberg, 1848-1936, stayed with RMH’s family during a period in 1865, and thanks to his diary notes it has been documented that RMH was working with his writing ball already in 1865. Center: The master mechanic Christoffer Peter Jürgensen, 1838-1911, was responsible for converting RMH’s ideas into practical solutions and built the first writing balls. Jürgensen probably developed his latest model of the writing ball in 1879, the lower and wider model, and RMH was very enthusiastic with this model featuring both a ribbon and a platen and more similar to what we associate with a modern typewriter. I personally assume that Lyngbye’s model was developed and was ready for sale in 1885 and it was awarded first prize medal at the industrial exhibition in Copenhagen in 1888. The portraits of Jürgensen and Lyngbye were photographed at the Danish National Museum of Science and Technology by Jørgen Malling Christensen.

RMH’s daughters Engelke Wiberg, 1866-1948, and Johanne Agerskov, 1873-1946, through their very exhaustive research contributed with plenty of valuable knowledge about the initial years of the development of the writing ball. Together, and in a very meticulous way, they set up a showdown meeting false accusations put forward in public in 1924 alleging that RMH had stolen the idea of his invention from another person. To the right: The son-in-law of the inventor, Fritz August Bech, 1863-1948, also contributed enormously to keeping the memory of RMH alive!

- My assessment of the existing documentation in the shape of the old patent applications, original letters as well as information in articles by RMH’s daughters and his son-in-law, leads me to the conclusion that the above model must be the very first writing ball built – i.e. model no 1. The drawing was made by Dieter Eberwein on the basis of the drawing from RMH’s very first patent application, dated 25 January 1870. In the application text RMH writes that he has “sat sammen” a writing ball, and the verb can be translated as either assembled/put together/ or: made/built. In my view it cannot be interpreted in any other way but that he has built it, or had it built. This model is also the only one that might correspond with previous information that the first writing ball weighed 75 kilos. Copyright: Dieter Eberwein.

But: when may we assume that the very first model of the writing ball was built? And why on earth didn’t RMH present a patent application much earlier if he really had a model before 1870?

In an undated and unsigned article found among the papers left by his daughter Johanne Agerskov, probably written by her or by her daughter Inger Agerskov, we learn the following:

“When the very first idea about the “writing ball” took shape with Malling-Hansen we don’t know for sure, and the available documentation does not provide a clear answer agreed by all sources. The years 1865-67-69 are being mentioned, but it has not been possible to establish a definitive year. However, according to the latest investigations, it appears very likely that a model was constructed in a final shape during the winter of 1867-68 or the winter of 1868-69, but not until 1870, after Malling-Hansen having acquired his patent on the writing machine, was it displayed in public.”

I would consider it to be highly likely that the author of this article is absolutely right in concluding that the first writing ball was finalized sometime between 1867 and 1869, but the exact point in time is unfortunately still hard to establish. But, if RMH had a writing ball ready as early as that, why didn’t he apply for a patent earlier than in January 1870 so as to make sure that nobody could steal his invention? I believe the simple answer must be that RMH did not feel that he was ready and that he still needed to develop the writing ball further in spite of having made at least one model. However, sooner or later he had to present a patent application, even if he felt that he could still improve his invention. Perhaps he contacted the poly-technical environment only in 1869 and by that time was encouraged to patent the writing ball, or maybe it became absolutely necessary to have a patent in order to acquire financial support to develop the invention further? The fact is, at any rate, that RMH continued to work intensively to improve his writing ball in the period after the presentation of the first patent application, and he continued to work with the construction of the writing ball up until the latest model that he himself designed for the world exhibition in Paris in 1878, at which his latest model, now with a ribbon, won a gold medal and received excellent comments. At this exhibition, by the way, the competing American “typewriter” produced by the Remington factories won only a silver medal. One might well ask what on earth made an inferior typewriter emerge victoriously in the commercial competition. But the answer to that query belongs to another article…

Considering the time it must have taken to put together the partially rather complicated patent application text as well as to make the drawings for the application presented in January 1870, we can with a high degree of certainty establish that at the very least there must have existed a finalized writing ball in 1869 – and probably earlier. I would venture that the winter of 1867/68 is a very probable period of time for that to have taken place. Many sources also claim that the writing ball was exhibited in Altona in 1869[1], and even if we don’t have irrefutable proof of this claim, it is still difficult to reject the information, since it also appears in an article by RMH’s daughter Engelke Wiberg, and she must be regarded a reliable source.

In summary: The machine that many people hitherto have regarded as the very first writing ball – the wooden box model shown in public on 8th of September 1870, is far from being the first writing ball ever built. It was probably the fifth version of the writing ball.

No 1: The prototype, built into a table, the paper cylinder being moved by means of a pedal. Circa 1867 – 1869.

No 2: Writing ball with flat surface, featuring a screw mechanism with a handle for line spacing and manual movement of the ball. Circa 1867 – 1869.

No 3: Writing ball with a cylinder with a clock spring that had to be wound up with a key. February 1870.

No 4: Combination model with a helical spring and two inbuilt wet batteries. March 1870.

No 5: The “official” box model with an external electrical battery. August/September 1870.

Oslo 08.11.2009

Sverre Avnskog

English translation by

Jørgen Malling Christensen

[1] JMC: Johanne Agerskov in her leaflet “Who is the Inventor of the Writing Ball” (Copenhagen 1925; in Danish), page 31, explains as follows: The German magazine “Zeitschrift für Büro-Bedarf” had an article about the writing ball with the information that the writing ball had been exhibited at the “Allgemeine Industrie-Austellung” in Altona in 1869. The Author, Mr J. Burghagen, had this information from a book entitled “Die Schreibmaschine”, published by Mr Otto Burghagen, the founder of “Bürobedarf”. He added that “Bürobedarf” no 76 of October 15, 1904 had a comment on the writing ball and stated the year of the invention as 1865. Mr J.Burghagen, however, had checked the exhibition lists from Altona 1869 and found that the writing ball was not included. Furthermore, Engelke Wiberg in a letter to Prof Hannover of 26 May 1924, comments concerning the information about Altona 1869: “It is likely that a friend of my father’s (I don’t recall his name) showed the writing ball in Hamburg at a company called “Donner & Co” in 1869 to representatives of the newspapers and magazines, and this demonstration was possibly related to the Altona exhibition; but since the patents were acquired only later, the idea of partaking in the exhibition was abandoned”.

We may add that RMH worked 1862-64 at the Schleswig Royal Institute for the Deaf-Mute, and during that time – according to his daughters Engelke and johanne – he made friends in Altona and it is not at all unlikely that these connections helped him to exhibit – or prepare to exhibit - in Altona.